So, you just finished your first Agile project in a Waterfall organization. Now what? Let me put my Agile Coach hat on and tell you, “It depends.” It depends on whether or not it was a positive experience and how supportive the overall organization is of this “Agile thing”. Let’s run through a few possible scenarios.

Agile Sucks

You may be one of the many people whose first exposure to Agile is a negative one. Maybe your team was uncooperative. Maybe there were too many practices that were too new for the team to successfully adopt. Maybe the organization was so un-Agile that your team got exhausted from trying to swim upstream the whole time. Or maybe your team never really became an Agile team; you were a bunch of silo’d individual contributors with Waterfall mindsets trying a new front-end to the same process you’ve always used to get the job done. Whatever the reason, all you know for sure is that Agile sucks. It simply does not work; not for you, maybe not for anyone.

As an Agile Coach, I am sincerely bummed if this was your experience. I wish I could have been there to help make sure you knew why you were adopting Agile, not just how to go through the motions. I wish I could have been your heat shield, to protect you from the Agile defeatists and remove organizational impediments for you. I wish I could have helped you through the forming and storming stages of a team into norming and performing, so that you could benefit from a team who, corny as it sounds, was greater than the sum of its parts. I wish I could have helped you learn how to continuously improve not all at once, but incrementally.

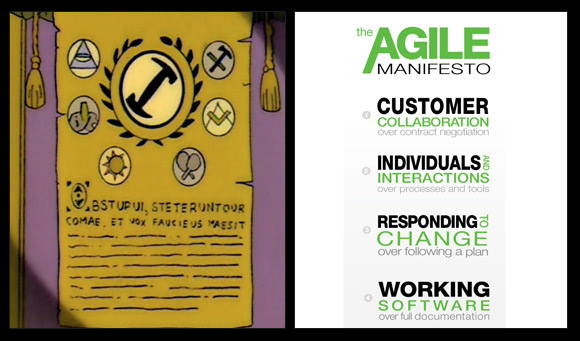

But I wasn’t there, so what will you do? I hope that you will take pause and consider the possibility that those Agile proponents can’t all be crazy. What did they do or have that you didn’t? What might you have missed? Get involved in virtual and physical Agile communities, remain open-minded, and stuff your toolbox with as many practices and approaches as you can. Study the Agile Manifesto and its principles and recognize that what it’s defining is a mindset, not a methodology. You have to be Agile before you can successfully do Agile.

Agile Recipe

Maybe you had some success with Agile – or at least you think you did – and you want to keep doing it with all your future project teams. What really happened is you ran a successful Scrum project, and you’re ecstatic that you found a working recipe that will turn any team into a high-performing team. The team followed the Scrum Guide to the letter and there’s no doubt in your mind that this is what Agile is all about. Agile is Scrum, Scrum is Agile. If you follow the exact same approach, you are confident you will have similar results with your next team. After all, this is the same company, same culture, same organization support and/or impediments. Why shouldn’t you expect the same results?

The short answer is because it’s not the same team. Even if some of the people are the same, if the make-up of the team isn’t exactly the same then it’s a different team. You’ll be starting back at the forming stage with a new backlog, maybe even a new Product Owner, and there’s no guarantee that this group of people will interpret and embrace the Scrum Guide the same way the old team did. Hopefully you learned enough about teaching, coaching, and/or facilitation from your last team that you can guide this new team through the same pitfalls in a faster, safer way. Hopefully you learned Servant Leadership skills that will help you get buy-in from the team to try this new thing. Hopefully.

Hopefully you learn by the end of this project how much more successful the project would have been if you would have kept your previous team together. There is a cost associated with breaking up a high-performing team and knocking everyone back to the forming stage. There are also reasons that you may want to incur that cost in order to reap specific benefits, but “because the project ended” is not one of those reasons.

Keep the Scrum Team

Not only did you have success with the team, the team became a family. You are now a high-performing Scrum team that knows the process and each other so well that you couldn’t dream of breaking them up. You manage to keep the team together for the next project, and you hit the ground running.

This is great, but you have to be careful. If you have decided that Scrum is the be-all end-all of Agile then, eventually, the team will begin to stagnate. Scrum ceremonies will become ritualistic instead of productive, thought-provoking team activities. Group-think may begin to crop up, and the electric feeling of respectful debate will flicker out of the team. Some team members may become too comfortable, others restless. If you don’t do something, you’ll lose everything you fought to keep.

My hope is that you learn that Agile isn’t about following a recipe. It’s about starting with a recipe and making it your own. It’s about evolving the way you cook, trying new flavors, and learning how to transition from cook to chef. Hopefully you find all the success you were looking for and more, because our successes motivate us to keep going, keep trying.

Become comfortable with mining for conflict and facilitating conflict to unearth change that will make the team better. Stay in tune with the latest ideas and do your best to keep the team in the “Learning Zone”.

Grow the Agile Team

|

| credit: universal studios |

Perhaps you’re one of the rare few who, by the end of your first Agile project, recognize already that the team should be together and should not be limited to just Scrum. Perhaps you’ve already begun incorporating aspects of Lean, Kanban, DevOps, Lean Startup, Lean Enterprise, eXtreme Programming, or any number of other Agile approaches to help your team stretch and grow. You have a vision for how amazing your team can be – a unicorn among horses – and you recognize that Agility is a journey, not a destination.

The team can only become so awesome before running into major roadblocks within the organization. The team can become locally optimized, but the benefits will be limited until the entire system is optimized. After all, this is a Waterfall organization – you can run whatever methodology you like within your team, but there’s still an overall process that must be respected.

You’ll soon find that, in order to best help the team, you have to spend less time with the team and more time fixing the environment they live in. Maybe it’s the dependent teams – adjacent teams doing similar work or component teams, such as Security, Infrastructure, or Release teams. Maybe the Operations team is pushing back, trying to drive constancy at the sake of functionality. Maybe it’s the way work is approved and projects are formed that prohibit the team from responding to customer requests and market demands as quickly as they are capable. Maybe there are leaders or others in the organization that are afraid of change and, consequently, are passively or actively sabotaging the spread of Agile.

If you are successful, you will find that organizational Agility provides orders of magnitude greater than a single Agile team. You’ll find that what the team does rarely have as great an impact on their performance as the environment in which they operate.